Grandmother inspires youth to break “silencing” around the 1960s civil rights movement and organize for a stronger future

June 22, 2014

By Margie Thompson, Escribana

By Margie Thompson, Escribana

“I really believe I have a whole lot of my grandma in me. Even though she didn’t go to college, I know the stuff she went through, with her perspectives, her strength and tenacity…it’s hereditary.” Being well aware of the tensions around the brutal Jim Crow laws, her grandmother literally “watched from the window” with her job working for a wealthy white family. But she also joined the marches and even fed the picketers as resistance grew in the early 1960s despite the brutal backlash from police and many in the white community.

While “silencing” of the history of the civil rights movement has been all too common for decades in the wider community in Mississippi and beyond, for young people such as Amber Thomas the past and particularly her grandmother have served to inspire her as an activist.

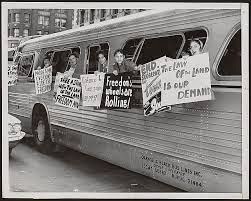

Freedom Ride 50 years go in Mississippi

Thomas is a young African American organizer and leader who also serves on the planning committee for the Youth Congress as part of the Freedom Summer 50th Anniversary Conference to take place June 23-29, 2014. Hundreds of activists — young and older — will travel to Tougalou College in Jackson, Mississippi to commemorate the civil rights movement. But the events will also serve as a launchpad for social activism to address key issues related to healthcare, education, voting rights and workers’ rights. Young people will be front and center with the Youth Congress, to also tackle topics such as gay rights, social media, and education (particularly the “school to prison pipeline”).

“For the Youth Congress, we are definitely encouraging all youth to speak about running for office, think about joining policy work, and to learn to organize around a lot of the issues that are affecting communities,“ noted Thomas.

Thomas, who is also a field director for Better Schools/Better Jobs, reflected back on her family’s past and looked to the future to describe her own start as a youth activist and her expectations and hopes for events at the Freedom 50th Conference. One of her main inspirations as an activist came from her grandmother, Rosie Lee Clark LeFlore who cleaned and cooked for a wealthy white family in Meridian, Mississippi. LeFlore was well aware of the tensions and issues of white supremacy with “the racist white people in the city and what they were doing and how they perceived African Americans in Meridian at that time.”

Thomas compared her grandmother to the black women in “The Help” (referring to the book and movie of that name), and how she “watched from her window” as the civil rights movement built momentum in the early 1960s in the face of the vicious backlash from police and other primarily white authorities. Despite terrorizing of blacks by white authorities, LeFlore also participated in protest marches, and cooked food for the picketers. She also refused to be silenced by “making sure all her children knew what was happening.” So after being raised in that household, Amber’s mother, aunts and uncles “made sure they passed that type of awareness and knowledge and thirst for change and goodness…along to us,” reflected Thomas. “It’s hereditary and I think I have a whole lot of her in me – that’s where I got it from, and it was part of my household. “

An ugly incident of racism and silencing in high school was an important turning point for Thomas, when the (white) principal of Murrah High School in Jackson, Mississippi refused to allow the nearly all-black student body to establish a black history program, claiming that with all of the activities in the wider community and state around Black History Month, there was no need to do more in the school. In response, Thomas and other black students filed a complaint with the local NAACP, then began organizing and protesting by wearing poster boards around school, printing t-shirts, etc.. They eventually were called in to talk to the superintendent of schools in Jackson, and the result was establishment of a black history program. Thomas was a natural leader, and was one of the main organizer of the campaign.

“It was my first taste that if you stand on what’s right and have pure thinking, things can really change and after that things have just been keeping going,“ she said.

Thomas’ struggle with the high school principal is an example of “silencing” of racial tensions at a more subtle level, through cultivating the idea that society has become “post-racial” or “colorblind.” Opponents of programs that focus on a particular race (such as Black History Month) contend that they only serve to stir up racial tensions (which often exist already). Thomas noted that while in her experience many in the black community are well aware of the silencing, and talk about the past among generations and connections to present day struggles, “In some circles [the assumption is] if they ignore it, it will just go away.”

One result of such silencing is that while people may be very conscious of racism, “some don’t even know or grasp that there are systems in place to keep them where they are,“ noted Thomas. “We have a lot of the same problems [from the 60s] but the method [used then] of solving problems doesn’t really work today. To take to the streets is a great way to show injustice but we also have to jump in and commit to seriously educating ourselves and saving money and rearing our families in proper ways and change policy and voting and having conversations.”

Despite years of struggle for social justice and many major gains, large inequities remain in Mississippi for African Americans, with public education a case in point. Mississippi ranks near the bottom on a number of educational achievement scales.

Thomas is also a field director with Better Schools Better Jobs, which works to raise awareness about major disparities in public education in Mississippi, much due to lack of funding that violates state law and the rights of African Americans in particular. “Better Schools Better Jobs was created to amend the state constitution [through a ballot initiative] to give all children the right to a fully funded education,” noted Thomas.

A state law called the Mississippi Adequate Education Program passed in 1997 established a formula to give equal funding to all school districts for instructional materials, teacher and staff salaries and operational costs (facilities). But districts with more black students were “nickeled and dimed, an historic trend over a long time,” leaving them woefully underfunded, according to Thomas. Such underfunding has contributed to a $1.5 billion shortfall in public education funding, according to the Better Schools Better Jobs website. The goal is to put a referendum on the ballot in November 2015 that would require the legislature to spend 25% of new growth to fully fund schools with a constitutional amendment.

“We know that the best education is very important for each child …they become a better person…and have a chance for a better life. And education gives them that chance,” said Thomas. She explained that they see this campaign as part of a larger struggle to create greater self awareness among people, to make stronger and more creative communities, “and a better place for every single person.” Quality education will help boost educational attainment and enable students to become highly-skilled workers and get better jobs, thus contributing to make the state a more competitive and stronger economy.

end

ESCRIBANA is covering the 50 Year Anniversary Conference in Mississippi Alabama from June 25-28, 2014. For more features go to escribana,org

http://escribana.org/grandmother-inspires-youth-to-break-the-silencing-around-the-1960s-civil-rights-movement-and-organize-for-a-stronger-future/